Treated But Not Cured

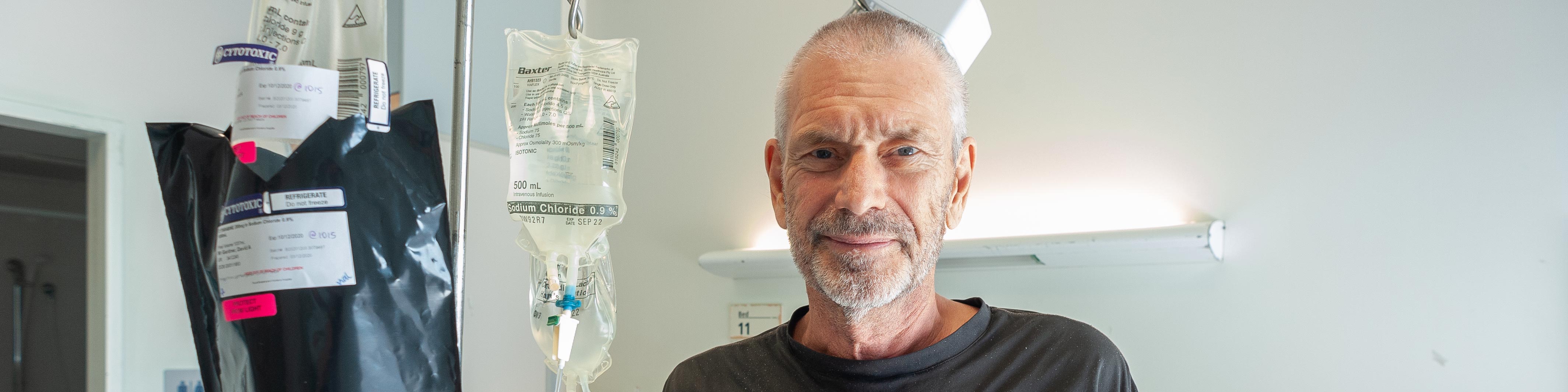

Consolidation, Round One

Black, black, exhaustion, darkness, nothing, no energy. I am almost indifferent to this disease. The hospital bed is neither comfortable nor uncomfortable. It does what it was designed to do. There is no pain, just a fever, but this treatment has drained me to my soul. Three months is a long time in a hospital bed and I am tired. Tired of the treatment, tired of the hospital, tired of mentally fighting this invisible but all-too-real monster called Acute Myeloid Leukemia.

I have no idea of the hour but it must be late because the corridors are silent and it seems like they've been this way forever. I've been abandoned. I am neither asleep nor awake just slowly falling in a lightly-drugged-out haze, a thousand miles above earth, falling slowly, almost imperceptibly faster every hour that passes. Up to now I've been able to float above it all, seemingly on the power of my own positive thoughts. I've not accepted that this disease will beat me and I've known I can stay up here as long as I want – so long as I really want. But tonight there is no will left, no buoyancy, no lightness, just a slow descent into the blackness, alone.

So alone. I ache for a human touch, a voice, some point of reference. There is no one.

The treatment I'm having was first used against leukemia in the 1970's, half a century ago. Sure, it's been refined over the years and today a trained haematology team has taken me within a hair's breadth of death in their efforts to eradicate the cancer cells in my bone marrow and give my healthy cells a chance to re-establish themselves. AML is 'incurable, but treatable'. 'We hope for a cure' they say, but they can never tell you you're cured. It doesn't work that way. Instead, the talk is about MRD, Measurable Residual Disease, and if they can't measure it then they can't treat it so you are 'in remission'. Until you're not. And then the treatments start again. But nobody ever says 'you're cured'. The chemotherapy has killed my innate immune system. Fevers and reactions caused by the drugs and sometimes by infections are common. That's what I'm experiencing now. This is the second time they've done this to me and it's not as bad as the first round, so let me go back a couple of months.

Induction

The first round is called 'Induction'. The idea is to estimate how strong a dose of idarubicin and cytarabine they can give without killing me and the hope is that it will be enough to wipe out the leukemic cells. It takes 3 days to infuse the drugs via a line inserted in my arm that carries the drugs close to my heart for distribution to the rest of my body, and I feel fine. No reaction at all. The drugs don't work immediately though. It takes about ten days for my white blood cells to succumb to the chemo, and as the lights go out in my immune system the fun begins.

One evening the nurse takes my obs as usual. My temperature is a bit high but I tell her I feel OK. She leaves and almost immediately I'm not OK. I am hot and light-headed and then my body starts shaking. I reach for the nurse call button but the damn thing has hidden itself under the bed somewhere. I am shaking like a puppet tied to the end of a concrete vibrator. This is spiralling out of control by the second. In desperation I dive over the edge of the bed, find the remote, hit the call button and just hang on ...

... a strange room, where am I? people stand around, staring, something happened ...

... I am in bed, an accident? who are these women? that one is extraordinarily beautiful! ...

I am naked, hot as hell, lying on a refrigerated bed with a fan blasting ice cold air over me while five women stand about talking to each other in an alien language. I mean a REALLY alien language, worse than Dutch. I cannot understand a single word. There are tubes going in and out of me. Bright lights illuminate everything, nobody smiles but I don't feel the slightest fear. I should be freaking out! But I'm an observer rather than the subject of this weird experiment.

Occasionally, I make out a word and it gradually dawns on me that they're speaking everyday English. My brain has been addled, but bit by bit I begin to recover and understand.

"(something) (something) name?" says the tall woman in the white coat, looking at me.

"av rdnr?" I reply hopefully. I try again, "Dav 'rdner"

"Good! Do you know where you are?"

"horse pital"

"Yes! Why are you here?"

"Wot?"

"Why are you in hospital?"

"d'no. Axdnt?"

An hour later I am almost back to normal and learn that I had a 'reaction'. Nobody knows why. Maybe infection, but all the lab tests come back negative. It's why they keep you in hospital during and after this kind of chemo. My temperature hit 41.7C. Not quite a record, but a personal best. I don't know how long I was out, maybe ten minutes. Long enough for them to get all the refrigeration gear in place before I woke up.

That was the highlight of my 'Induction'.

How I got here

So how did I get here, to a hospital in Melbourne Australia, from sailing down the African coast?

I knew, in Africa, that something was amiss. I'd had a succession of health issues and Tanzania is not a good place to be unwell. As soon as the season changed and South Africa opened its doors to yachts after the initial covid panic I went south in the company of two other yachts, all of us heading for South Africa, 1,650 nm from Tanga to Richards Bay.

The trip was easy until the last two days. The traffic around Richards Bay meant I had to forego sleep and set an alarm for 20 minute naps. By the time I reached the entrance to Tuzi Gazi, the international arrival dock for small boats, I was exhausted. It took twenty minutes to drop the mainsail, something that normally takes two minutes. I then motored towards the dock, completely forgetting that I needed to dig out lines and fenders. They hadn't been used for over a year and had sunk to the bottom of the lazarette with sails, sheets, halyards and everything else piled on top. I finally got some lines out and in place and headed for the concrete wharf. I misjudged the approach completely and crashed into the dock rather badly. But I was there.

A stranger, whose name I later discovered was Michael, took my forward lines and Roy took the aft lines. I fooled ineffectually with fenders and then went downstairs and collapsed into bed.

South Africans have a wonderfully positive and engaging attitude to trouble. Nothing is too hard. Jenny Crickmore-Thompson runs a fabulous WhatsApp group that keeps traveling yachts informed of everything and when people found out I was unwell the help came flooding in. Michelle at Zululand Yacht Club took charge of me. Her husband and son moved Anjea from Tuzi Gazi to the club marina. Michelle and other club members then ferried me to doctors and hospital, shopped for me and even cooked for me!

Other yachts helped out with everything from washing clothes to just checking to make sure I was OK. Roy, who sailed down from Tanga with me, was there every day; Janneke and Weitze were a constant presence; Jacolette and Natasha drove me to town for medical appointments and arranged a ride to Durban; my South African friends, Walter and Jacqui, whom I first met in Australia, were now home in Port Elizabeth and provided assistance from afar. Arthur from Tanzania has good friends at this yacht club and ensured I got all the help I needed. It's an amazing network and it lifted my spirits and solved a lot of practical problems.

A few days later, after a bunch of preliminary tests, I was admitted to hospital and received five units of blood to keep me going. The doctor who took charge of my treatment is a urologist but his diagnosis was not prostate cancer, as I feared, but something far worse: leukemia.

It hit me hard. I was fucked. Google 'leukemia' and you get nothing but bad news. I took it out on those around me, the nurses and medical staff, the other patients. Anyone who asked me 'How are you?' got the unadulterated truth laced with a shot of acid sarcasm, a wall of hate and an explosion of anger.

Two days later, after insulting an orderly because she wished me a good day, I realised that being an arsehole was not the answer. I withdrew, and eventually decided to make it my mission to improve the lives of those around me in some small way instead of bringing them down. Yes, I was unwell, but nothing had really changed in my life except that now I knew for sure that I was mortal.

There are no Haematologists in Richards Bay. Phillip, the Urologist, turns out to be a great ally. He steps up and smooths the way from the initial diagnosis thru more testing to seeing a specialist in Durban. The final diagnosis is AML, Acute Myeloid Leukemia and I have about a twenty-five percent chance of living another five years, with treatment, and that's the thing. Treatment in South Africa is not free and I do not have insurance here, only in Australia. A standard course of treatment here in South Africa would cost every cent I have and a whole lot I don't have. It's out of the question. The only option is to get back to Australia.

I call the Australian High Commission and am put in touch with Tracey who makes things happen. Later that night I'm woken by a call from a woman with a very strong accent on a very bad phone line. I make out she's with Emirates Airlines and is offering me a flight from Johannesburg to Brisbane. I try to tell her I want a flight from Richards Bay to Melbourne, not Johannesburg to Brisbane. After much to and fro battling the poor connection and her limited English I succumb and book the Jo'burg – Brisbane flight. At least it gets me from South Africa to Australia and I can worry about connecting flights tomorrow.

Two days later I get a lift from some girls heading down to Durban for work and pile on board a fully packed flight to Johannesburg with so many coughing, sneezing passengers that I'm convinced I will walk off the plane with covid. The flights to Dubai and on to Brisbane go smoothly. Covid ensures that the international terminals are deserted and I have a row to myself on both flights, so I simply stretch out and sleep for most of the time.

Landing in Brisbane is quite an experience. I will never again get such royal treatment. As soon as the door is opened an announcement is made for us to please stay in our seats and then I hear my name. I make my way to the front where a uniformed paramedic and a guy in a crumpled brown suit are waiting for me. We are first off the plane, even before first class. We get to customs and Crumpled Brown Suit ignores the queue, ignores the scanners, ignores the uniforms and we just walk on thru. Officials nod as we pass. When we get to immigration Crumpled Brown Suit walks up to one of the windows and says "Make it snappy". The official studies my passport, nearly panics when he can't find my entry into South Africa, relaxes with obvious relief when I point it out, buried among a dozen other imprints from various African ports, and I'm officially back in Australia. The only delay was waiting for my bags to tumble down the shute, and even then my bags were first out. How did they manage that? Tracey and all the other people behind the scenes in DFAT and other government departments have done their job thoroughly.

I step into the waiting ambulance and we head for the Royal Brisbane and Women's Hospital, the leukemia center for Queensland, where they install me in the Infectious Diseases ward. This is where I will spend the mandatory 14-day covid quarantine. I cannot go to Melbourne because Melbourne is not accepting flights or people from anywhere so I have no choice.

An Infectious Disease

The cleaner in the Infectious Diseases ward has been cleaning this ward for 30 years. He's a mine of practical information: how to get good hospital food that isn't on the menu, where and when to get a decent coffee, and which way to vote at elections. He educates me about the importance of his job, but really what he loves is to have a good chat with whoever the current ward resident may be. I'm a bit disconcerted to hear that the previous occupant had Ebola, and that most of the patients passing thru this ward had AIDS. The only reason I'm here is because of covid quarantine restrictions. As soon as the quarantine period is over they will move me down one floor to the haematology ward which, I am assured by all the staff, is a lot more fun.

And so it proves to be – 'fun' in both the positive sense of the word, and in the Chinese 'interesting times' sense.

Ward 5C, Haematology

Leukemia is hard. The treatment is awful, the side-effects frequently worse than the disease and the outcome is mostly fatal. The nurses that choose this particular ward are special. They really enjoy their work. At first I am suspicious that their good humour is some sort of professional nursing jollity. And in a way, so it is. They laugh and horse around, talk about TV shows, and their favourite actors, and dress up in silly costumes for any special occasion. But it is also deeply ingrained in their approach to work. Everyone helps everyone else. Everyone stays positive. Everyone checks everyone else. Three times. Nobody ever says "Why are you doing that?" in a negative way. Instead, it's always positive, always upbeat, always aimed at getting the best outcome in the best way in a workplace where tragedy and horror are everyday occurrences and they are dealing with drugs that could well be fatal to themselves if they're mishandled. It's a philosophy by which they live and it is definitely infectious.

While I was upstairs in Infectious Diseases they started me on a '7+3' regimen of chemotherapy. Now I am 'home', in Haematology, and here I am nothing special. They have timed it perfectly: I am now neutropenic, meaning my immune system has been wiped, and I'm feeling the effects of the chemo. I'm tired, sleep most of the time, and drop any pretence at staying fit by walking the corridors and pedalling the exercise bike I found hidden in a storeroom. I'm bed-ridden. Days and nights blur into each other. I try to keep track of the daily blood tests, looking for a tell-tale bounce in my neutrophils but they remain stubbornly at 0.00. They transfuse me with blood and platelets to make up for the blood cells killed by the chemo, inject exotic growth factors to stimulate my remaining bone marrow stem cells into making more blood, fill me with prophylactic antibiotics, antivirals and antifungals – anything that will reduce the chance of an infection that could wipe me out. And we wait...

Days go past and I wish for nothing but for them to pass. I have no other desire. Now, is all I have. The present moment is everything. But I've been infected with positivity. I strive in every encounter with a nurse, cleaner, doctor or medical student to make up for my past by improving their lives in some small detail. Is it deception? Fakery? Or invention? Seeing something latent in a person or situation and making it so, bringing it out.

The staff wear silly hats and try to infect me with some seasonal merry-making. It doesn't work, but I am not immune to the festive atmosphere of Christmas. The most depressing aspect is the food. It is supposed to be Christmas Dinner and comes with a paper hat and cracker but it's impossible to distinguish the food from any other day's bland, overcooked, lowest-common-denominator subsistence fare.

At day 24 my neutrophils bounce. The count is 0.07 x 10-9/L. Next day it is 0.36, and I'm off. The relief is incredible, everyone relaxes, nurses drop their professional smiling façades and chat naturally about their boyfriend or their kids. They ask me questions about Africa, tell me stories of their home country or their travels, and joke about covid. It's a milestone. One of several to come, but a milestone nevertheless. The only downside is the pain in my bones, especially my hips, as the bone marrow recovers.

A Holiday

The promised holiday has arrived. I was told I'd get a break from hospital after Induction and this is it. It's 30 December, just in time for New Year's Eve. My friend Kay picks me up from hospital and we head down to the Gold Coast. Next day Kay takes me for a walk from her place along The Spit. The air is wonderful, the sun divine, and the boats on the water remind me of what life was like just a few months back. I overdo it and am exhausted by the time we return.

The following day Kay provides a guided tour of the places I used to hang out when I lived here for a year in 1974. We swap memories of how the GC used to be. The changes are massive. All the old weatherboard Queenslander holiday houses have either been tarted up and are now worth a fortune, or pulled down to make way for palaces and apartments. Tugun, with its unforgettable servo that made the best hamburgers ever, is unrecognizable. We go to bed early and I completely miss the covid-subdued fireworks that ring in 2021.

It is New Year's Day and I have a flight booked to Melbourne. Covid prevented me from returning directly to Melbourne when I came back from Africa, but now I can travel there and it's arranged for me to be admitted to Royal Melbourne Hospital and for my remaining treatment to be managed by specialists at Peter MacCallam Cancer Center.

I catch the train to Brisbane Airport, the plane to Melbourne and am picked up at Tullamarine by my sister-in-law Kareen. Her little van has only two seats so she's left my brother, Jeff, at home. We make our way back to Maldon where I will be staying a few days with my very dear friend, Ellen, before returning to Melbourne for the next round of treatment.

My soul yearns to be back on Anjea, but if there is any fixed place I call home on this planet then this is it. Central Victoria's box ironbark forest has been butchered by gold diggers for 150 years. It is hard country to love – dry, hot in summer, cold in winter, twisted, stunted eucalypts, a lot of introduced species, diggings everywhere, the remains of mines, a rocky, hacked-about, marginal land that breeds hardy plants, animals and people.

A week or so later I get a call from RMH to say they have a bed for the next round of treatment: Consolidation, Round One. Did I do the right thing coming to Oz? Sometimes I think the enormous effort going into the exercise of trying to cure me of leukemia when there is no cure is just capturing what little time I have left and making a guinea pig of me. I want quality of life, not merely life extension. All the papers I read and all the clinical trials are focussed on extending life. But if that life is spent in a hospital, or in fear of immanent need for a hospital, then it isn't what I want. If I'd gone back to sailing after the blood transfusion in Richards Bay how much time would I have had? A month at least; three months maybe. The clinical trial I am looking at sounds promising on the surface because I may get 20 months. But how much of that is going to be sailing time? And how much will be in Melbourne being poked and prodded by researchers trying to publish a paper, or clinicians optimizing their stats. I understand the forces at work. I know how medicine operates. I can also see just how easy it is for a patient to lose purpose and yet continue living.

Anything but Darcy

Darcy is from North Queensland. He's had AML for several years and went thru the same initial treatment as me, followed by a stem cell transplant. Between bouts of Graft vs Host disease (GvHD) he smokes dope and hangs out with his friends. One of his friends won a serious amount of money in a lottery and is in the process of blowing it all on having a good time, so he gets a few scraps from that table. He is convinced that he needs to go to Mexico and buy a large amount of marijuana, from which he can extract an oil that will cure him.

Darcy has experienced some serious side-effects over the past several years: his legs are red and scarred from an inflammation that covered them to his crotch and eventually removed all his skin. A mosquito bite resulted in a medivac lift by helicopter from North Queensland to Brisbane where they stabilized and treated him. It's an everlasting cycle. I can see myself in Darcy. What else would I do with such an uncertain medical prognosis? Find a nice place to camp and drink booze or smoke dope to pass the time between bouts of GvHD. I get it, but I don't want it.

GvHD is a complication of grafting stem cells, the most recommended therapy for AML, and the closest thing to a cure that clinical medicine can offer. Good bone marrow stem cells are harvested from a compatible donor and injected into a patient in the hope that the donor cells will replace the leukemic stem cells. Amazingly, it sometimes works. But there's this little complication call GvHD where the Graft (the donor stem cells) turn against the Host (the patient's body) and attack it as if it was a foreign body, which to them it is. Remember, the donor cells come from someone else, so the body they are now hosted in is actually foreign to them.

The Haematologists recommend me to consider a stem cell graft. They want to check out my brothers for compatibility. Stem cell grafts can keep you alive, but I do not want to be Darcy.

Consolidation, Round One

I get nearly two weeks holiday before being admitted to Haematology, ward 7B, at RMH for the second round of chemo, Consolidation Round One. This hospital is clearly not the same as Brisbane, but this is Melbourne where black is the dominant fashion colour, apart from hair of course, which is green.

They start into the chemo immediately and as before I feel no ill-effects until after I go neutropenic. And as before I react to something: the treatment? an infection? the chemicals? nobody knows but I lose all energy and my body shakes with fevers and chills.

I hear the door click, and become aware of another person in the room.

"Hi David, I'm Annie, the Resident tonight. Sorry, it's taken me a while to see you. We have some problems on the ward tonight."

"Oh, that's ok," I lie, "there is nothing you can do for me anyway," which I think is true, but will prove to be false.

"Are you feeling down?"

I launch into a blurry, confused description of my depressed state. I don't remember what I say but I remember her taking my hand and that it was incredibly important and gave me strength. Strength enough to sleep.

That night I reached a new, special, low. Normally, my low points are short and not so deep. That night I discovered what lies under the carpet, what I hide from myself and try not to think about.

Consolidation, Round Two

I'm at Ellen's place outside Maldon in Central Victoria being cared for with way more attention than I deserve between rounds of chemo.

I awaken tired rather than refreshed, depressed rather than uplifted by the dawn of another day in paradise. I call it chemo brain, but truthfully, I am not sure whether it's the chemo or the whole depressing saga that's wearing me down. I take the train to Melbourne for another bone marrow biopsy. BMBs are not fun but this time I discover a silver lining.

In the past I've said "no" to the green whistle. This time the nurse is more persuasive. Methoxyflurane is a common fast-acting analgesic frequently carried by paramedics. They call it the green whistle because it looks like one, except you suck instead of blow. It is enormous fun! It's a better hit than Laphroig, but they need to work on the flavour – it reminds me of those really disgusting Kool cigarettes.

The results of the biopsy confirm another round of chemo is justified so it's back to RMH for a third round, confusingly called 'Consolidation, Round Two'.

Recovery

The last round of chemo went smoothly and finished 17 days after it started with only one day of mild fever. David, the Haematologist, says I can exercise freely once blood cell counts return to normal. On leaving hospital my cell counts are marginal and my fitness is at a very low ebb.

I push myself to walk from Ellen's up to Darkie's Hut every few days. It's less than 2km for the round trip but it's a steep walk to the top. The first day I get about half way before my legs turn to jelly at the same time as all oxygen is removed from the air I'm trying to breathe. I turn and stagger back to Ellen's.

A month later I am powering to the top, gasping for air when I get there, but recovering quickly.

Two months later it's too short; not enough of a challenge. So I pursue longer walks and start riding the bike I've borrowed.

Ellen introduces me to Nicky, the local policeman's wife, who runs a small gym in the shed behind the lockup. She keeps me honest by beating me up every Wednesday morning at 8:15. I am never late, even on winter mornings. Although she is gentle to start with the load increases every week. In the seventh week she pushes me hard. Cycling back to Ellen's, the last hill has suddenly become very steep.

It is early June and winter. At my monthly session with David Ritchie the Haematologist I have only one question: "What would you say if I went back to Africa on 1st August?"

"Get monthly blood tests, and one more bone marrow biopsy before you go. If that confirms you're still disease-free then no problem."

I had decided to go anyway, regardless of David's advice, and can barely believe, after all the chemo, tests, restrictions, caveats and warnings, that I might actually be able to do so with his support. From his point of view I guess I am a good stat: a tick in the CR column, Complete Remission. From my point of view this quiet, serious, polite, ordinary-looking man is a god: he has returned my life to me, for now at least.

With just the crudest tools: a poison derived from mustard gas, some antibiotics, and a few prophylactics, but with exquisite precision and confidence, he has curtailed the cancer and provided my bone marrow with a chance to regenerate. I am lucky that the particular flavour of AML I have was susceptible to this treatment; many other AML patients do not even survive to this point.

It is cold and blowy as I make my way thru the bush to the Rock of Ages, a local picnic spot, deserted today. The bush around me is in motion: trees bending, grass waving, a few brave birds soaring on the updrafts over the ridge, too far away to make out what they are. The sun is playing hide and seek with the clouds and I'll be lucky to get home dry, but I don't care. The air is cold and clean, my body feels good and life is sweet. I'm very much aware that all the medical care in the world wouldn't have saved me without this.

I've had food, care, a place to live, freedom from worry – all delivered with love from Ellen. The environment she nurtures and her nurturing of me has completed my recovery. It is now 181 days since my treatment started. There have been days of blackness, grey days of boring sameness in hospital beds, days I thought my strength had left me. There have also been days of hope and insight, days of learning, and now, at last, a remission from this disease.

I am lucky beyond measure to have a friend like Ellen, and to be able to contemplate a return to sailing.