The Queensland Coast

This is a sailing slog, with more than usual emphasis on passages and anchorages. I have tried to make it useful for Jean Marie, Arica and Beaujolais who are following us up the coast and have not been here before. Lesley and I have both sailed this coast a few times and are keen to move north pretty quickly to explore areas we haven't been. In this trip, our stays around the Whitsundays have been dictated partly by weather. We've had some strongish winds, rain and cloud, which tends to take the edge of sailing in paradise. Nevertheless, this is a remarkable stretch of coastline with dramatic islands, beautiful beaches, and some great dive spots. It is also prime cyclone territory and was badly battered by Cyclone Debbie in 2017. Airlie Beach in particular got hammered and still bears the marks.`

Apologies in advance for non-sailors as this slog is extensive and fairly detailed.

Pearl Bay

The entire Shoalhaven Bay area is a military reserve. Every so often the military decide they need to play some games and so they make it out-of-bounds to everyone else. They advertise that they are shooting 'live rounds' and that seems to keep everyone away. Fortunately, these impulses on the part of our military are fairly rare and in between times we yachties get to play here! It is uninhabited with no facilities: no phone or internet and limited VHF. But it is rugged, attractive and full of fish. When the military want to play war games they advertise it fairly well through the local VMR who broadcast warnings on VHF.

In the past I have used Island Head Creek as a shelter — quite a large, attractive and very well-protected inlet. But there are several other options in the area including Pearl Bay, a favourite of Lesley's. So this time we went to Pearl Bay. I was apprehensive because it is not as well-protected as Island Head Creek and other places, but I'm willing to give it a go. Pearl Bay is well-known for its population of painted crays.

We arrived early afternoon from Keppel Island after a very easy sail mostly under spinnaker. It is an excellent anchorage: pretty, and reasonably comfortable and protected, although it is subject to a bit of swell in south easterlies, and the swirling current means the boat is held up broadside to the wind making it roll a bit. However, it is nowhere near as bad as most of the island anchorages around here.

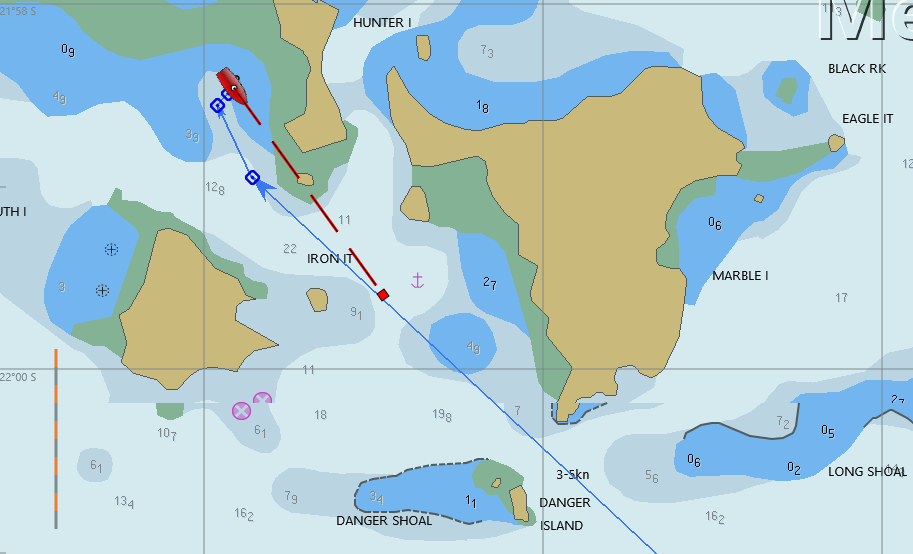

The approach looks intimidating with lots of islands and rocks. But everything seems well-charted. We keep our distance from the hard bits and experienced no problems. Coming in to the anchorage itself requires sailing through a narrow gap between an island and the mainland. The minimum depth here is 3m LAT. Stick to the middle course between the island and headland for the best water. If there is any tide running the current here can be quite strong, several knots, and it is this current that swirls around the small bay inside. The bay is quite small with good anchorage for only a few boats. The bay shoals towards the beach and towards the rocks on the southern shore. We anchored in the middle at 22 26.634 S 150 43.991 E. Depth here is about 3.6m at low tide. There are a couple of rocks and a sandbar shown on the charts. Tides here are 5m so you need to do your tide arithmetic.

Pearl Bay would make a safe anchorage in any S/SE weather, despite a bit of rolling, but would be uncomfortable in an Easterly and untenable in anything more than a light breeze from the north.

Jimmy on Tranquillity came rocketing into the bay mid-afternoon, did a circuit around and anchored inshore of us. We met him next day when we went over on the way to the beach for a walk. He knew about the crays and had some pots that he was going to try. We tried with a spear gun but the crays were safe because it was way too murky. We couldn't see to the end of our arm under water. We gave it one shot of about 5 minutes and left the crays in peace.

Later, Jimmy came over and we shared the last of our mackerel. We then climbed into his dinghy and went over to one of the steep little islands to our north west (not shown on the chart). Jimmy claimed there was a grassy knoll we could climb to from the little beach, but we couldn't find it so just explored the beach. Lesley and Jimmy harvested some of the plentiful oysters off the rocks. I find oysters slightly disgusting, unless they are the huge Tasmanian variety which somehow seem different.

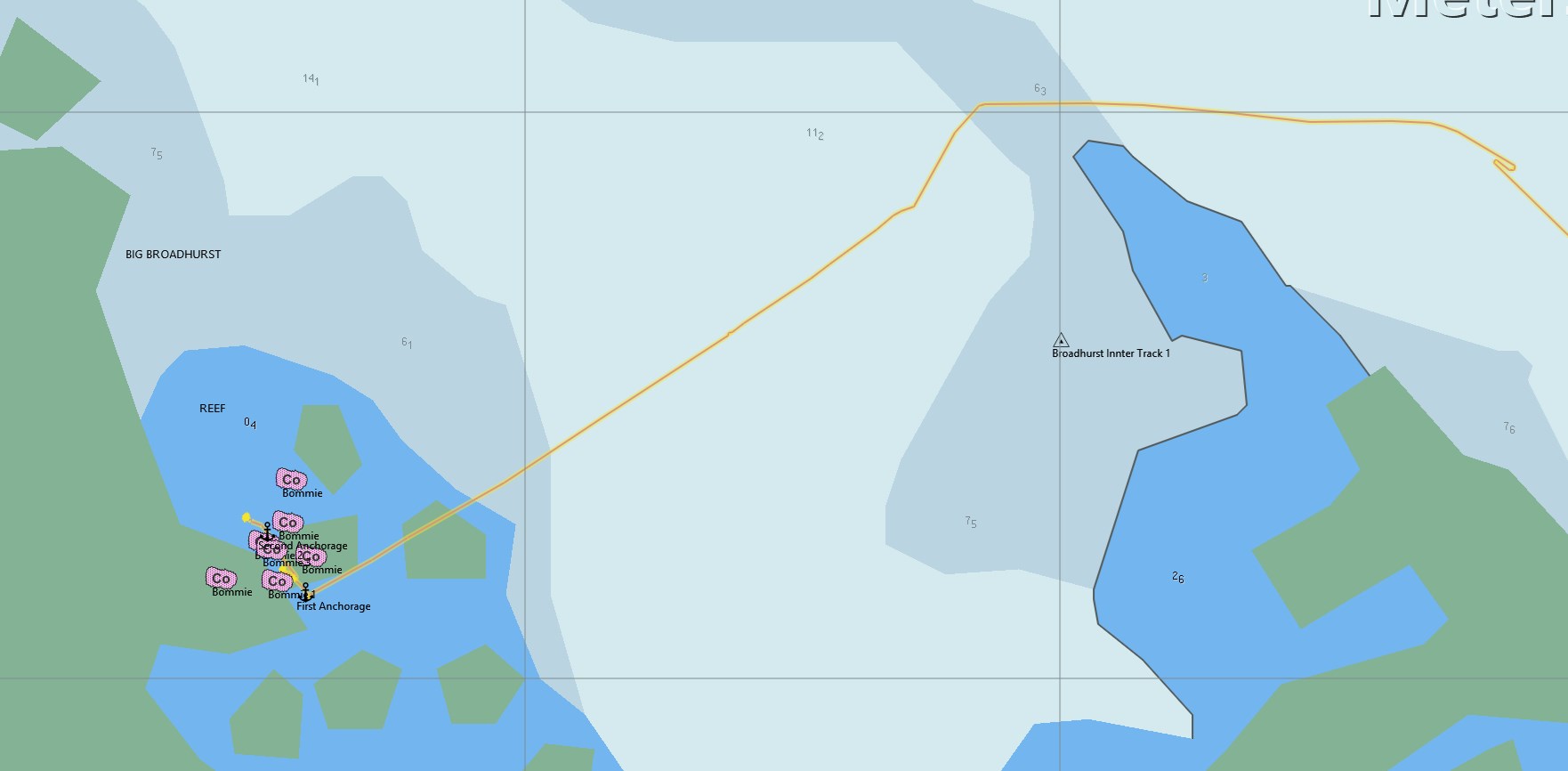

Our track in and out of Pearl Bay

Our track in and out of Pearl Bay

Hunter Island, The Dukes

A full moon, plenty of wind, and lots of sea to go with it, with more anticipated offshore. So although we left Pearl Bay for Percy Island this morning we decided en route to try The Dukes instead. A solo sailor in Pearl Bay, Jimmy on Tranquillity, suggested it, and it is excellent.

Jimmy said it got a good wrap in The Curtis Coast sailing guide. We don't have that, and Lucas doesn't say much about The Dukes except to watch out for fringing reef and foul ground.

On the way here we set a reef in the main and a full genoa. When we got offshore a bit we put a second reef in the main. For a while the wind was directly behind blowing a steady 18-20 kn and we poled out the jib. We sailed at 7 to 8 knots, more when surfing. Too fast for me but Lesley loved it. I don't much care how long it takes but she likes to get there fast! Anjea romped along and was comfortable. She likes Lesley. In addition, the full moon meant we had up to 2 kn of tide helping us, making 9 to 10 kn over the ground.

We approached The Dukes between Danger and Marble Islands a bit after the tide had turned and the current was finally against us — by 5 kn! Danger Island, according to Lesley, was where the ABC filmed the incredibly popular Danger Island TV series in the 1960's — the one with George and Jongo? Never heard of it? No? I hadn't either. Another thing missing from my deprived childhood. All I wanted was Dr Who and I Dream of Jeanie (but only after I turned 13, "Yes Master" — what a woman!) Lesley can sing the Danger Island theme song for you for a sip of beer.

A yacht was struggling to come the other way, motoring into the wind and taking a lot of water over the bow. They were thrown so high in the waves that the keel was partly out of the water. We groaned to imagine how uncomfortable they would be and swore once again never to go upwind! However, they managed a happy wave as they went past on the wrong side of us without giving way (we were under sail, they under power). We had to swerve to avoid hitting them!

Once through the channel between the islands the current eased a bit and the sea went down. By the time (about 2pm) we got to our anchorage at 21 58.4461 S 150 08.1877 E the current was just a couple of knots and the sea was flat. The anchor dug in without trouble. We agree it is a great spot, especially considering how terrible many of the anchorages along this coast can be. Why bother with the Percys? They were interesting once but never a good anchorage.

Hunter Island

Hunter Island

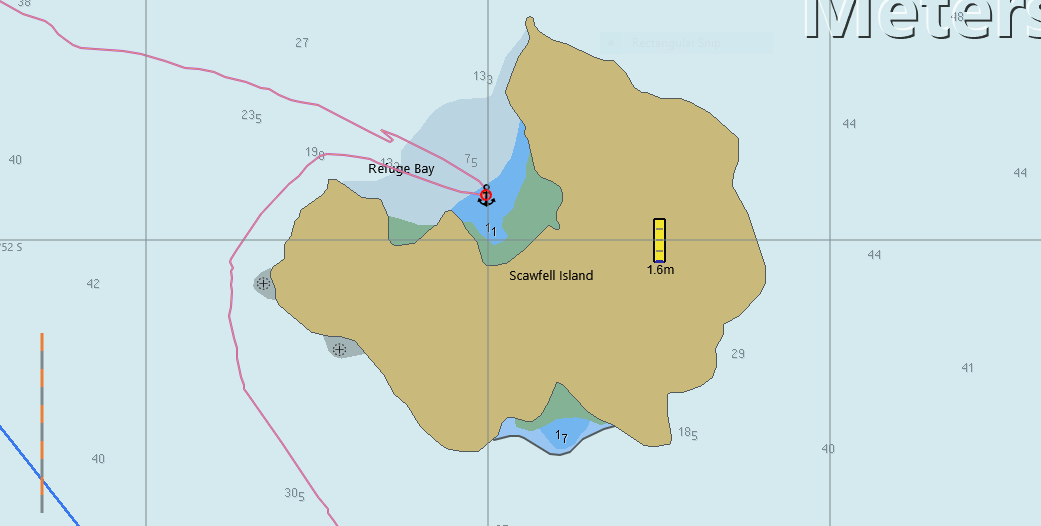

Refuge Bay, Whitsundays

An 11.5 hr sail took us from Hunter Island in The Dukes to Refuge Bay, Scawfell Island, just inside the southern limit of the Whitsundays. It was a long tiring day but the sailing was fast and we covered the 78 miles in 11.5 hrs, an average speed of just under 7 kn. Not bad at all.

The only hassle was Donald, the autopilot. Donald can't be trusted with great power. Everything will go well while you're on deck looking over his shoulder. But as soon as your attention drifts, or you go below, Donald's grip on reality starts to falter and then there's some sort of drama — a roundup or a gybe or Donald just drifts off on his own route and of course the surrounding instruments start tweeting like crazy.

So we spent some time trying to work out the whole autopilot system and make Donald more reliable.

- The hydraulic pump is an Octopus reversing piston pump, with a bypass valve to allow manual operation of the steering.

- The actuating piston is double-acting and connected directly to its own steering quadrant. There is a separate quadrant for the manual mechanical steering mechanism.

- The autopilot itself is an electronic box matched to the hydraulic pump. The motor rating of the pump is not specified but I worked out that it draws about 10A, and the Raymarine 200 autopilot is rated at 20A, so no problem there.

Donald has been acting strangely for some time but his behaviour is getting very much worse and the noise of the pump is much more noticeable. Finally, I decide to unload the sail locker, behind which is Donald's private lair, a small area behind a grating at the stern next to the rudder quadrant. With all the sails and ropes extracted I can unscrew and remove the grating and it is just possible for me to wriggle up there and scrutinize the situation. There are no oil leaks (good), no slop in the mechanics (good), the wiring looks fine, but the oil in the reservoir is about half full (less than good).

There are no marks or graduations on the reservoir and the manual has no indications about how much oil there should be, but I decide to top it up and bleed the system. Bleeding the system results in lots of froth and bubble in the oil reservoir (good) and it looks as if air in the hydraulics may have been the problem because of the low oil level.

We will find out tomorrow for sure but it looks like I may have fixed it. Fingers crossed.

Refuge Bay on Scawfell Island

Refuge Bay on Scawfell Island

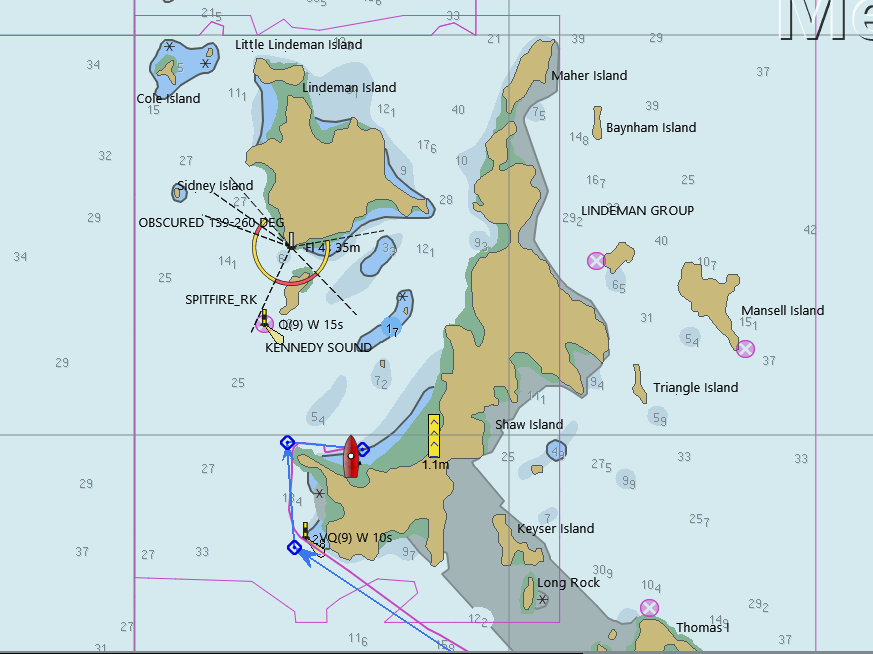

Shaw Island, Whitsundays

Donald is a reformed autopilot. Quiet, and not one single mad tweet today. We may have to rechristen him. Coming out of Refuge Bay the wind was behind us and came over the top of Scawfell Island, making it puffy and unreliable until we got clear of the island influence. The wind eventually settled into a southerly of about 15 knots and we sailed with a full main and poled out the jib to travel at just over 7 knots.

As we drew away from Scawfell some weather came over the island and raced to meet us. I fluffed the reef by hauling on the wrong reef line (I was sure it was the white one!). Anyway, we got it set eventually and continued on our way. The biggest gust of the squall was just 20 knots, so we got the reef in just perfectly.

After that the wind swung to the south and we were on a broad reach, my favourite point of sail because it is so fast and comfortable.

Shaw is one of the larger islands in the Whitsundays and there are many places to anchor along its long, indented, western shore. We chose to stop at the southern end and are currently anchored in quiet conditions with little wind and no swell. Unfortunately, the water is turbid, possibly because of the very strong currents swirling around offshore. So no fish — unless you can see them you surely can't spear them. This is our last opportunity for spear fishing until we are the other side of the Whitsunday 'Public Appreciation' zone. I guess they don't want us to accidentally spear any of their high-priced tourists. Or maybe they don't want us to upset them over their coral trout dinner by witnessing one being speared.

Shaw Island

Shaw Island

Hook and Hamilton Islands

After a few days in Airlie it is great to be back out on the water, but unfortunately the weather is not great for going out to the reef. Instead we are hanging around the top end of the Whitsundays trying to find moderately comfortable moorings.

When we first arrived we were keen to get in the water and so we picked up the first mooring we came to in Butterfly Bay. The dive was not great and the mooring was very rollie. Next day we sailed around to Blue Pearl Bay on Hamilton Island. I do not remember ever stopping here before and it's quite pleasant. The diving is unspectacular but we're out of the increasingly bad weather. This weather was not forecast.

There's rain and plenty of wind overnight. In the morning the swell starts to come round the point making life unpleasant. Our plans to go ashore for a walk are scuttled by yet more rain and so we decide to go around to Manta Ray Bay on Hook Island.

The short trip is uneventful. We have 3 reefs in the main and the staysail up, which is conservative, but turns out to be adequate for the conditions. It's quite gusty so if we had more sail we'd be over-canvassed in the puffs.

Manta Ray Bay is known to us both. It's a popular dive spot. The reef and rocks are ordinary but the fish are plentiful and large. It is also compact so we can swim from the boat without putting down the dinghy. We see whole families of coral trout, clouds of baitfish, some batfish, plenty of parrot fish, fusiliers, and lots of others. I didn't feel the jellyfish until one stung my lips. It was like a small electric shock, quite distinct and left an 'after-shock' that lasted a minute or so. They are small jellyfish, quite transparent and the tentacles are hard to see. There are hundreds of them and Lesley suffered more than me because she started without a 'rashie'. After a few minutes she went back to the boat to put one on.

We swam around the point to The Woodpile, a cliff-face that looks just like a giant's fossilized woodpile rising from the sea. The interesting stuff is a bit deep here, probably about 10m below the surface. Lesley says about 5m but I'm sure it was more than that. Anyway, too much for either of us to free dive comfortably for long.

Hook and Hamilton Islands

Hook and Hamilton Islands

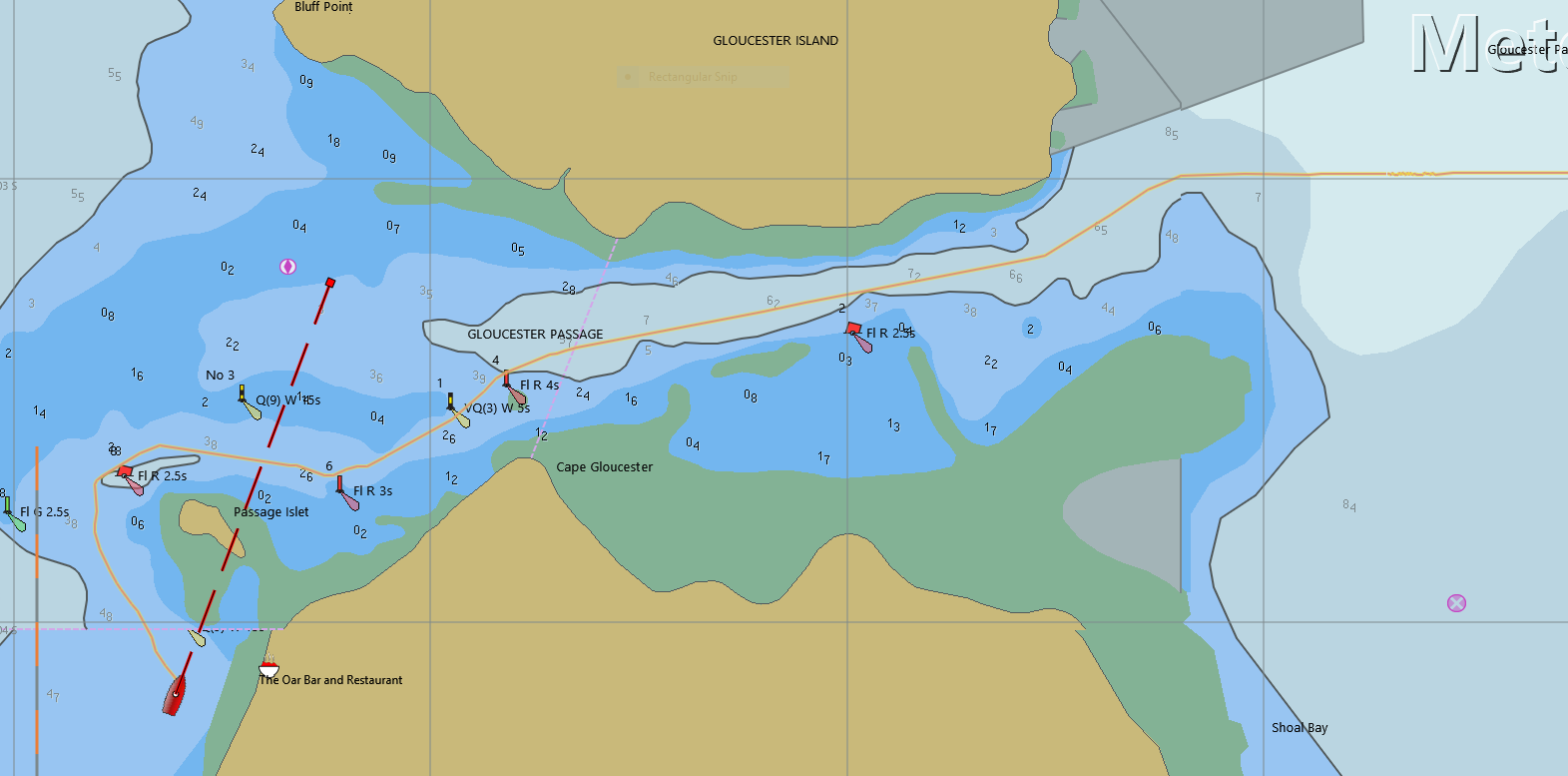

Gloucester Passage

The Oar is a bar and restaurant on the foreshore at 20 04.0438 S 148 26.6507 E on the mainland more or less opposite Passage Islet at the west end of Gloucester Passage. We anchored amongst the moorings, most of which were unoccupied when we were there. We probably could have picked one up but are tired of heavy, dirty mooring lines and prefer to anchor. Holding seems good in clean sand.

After an afternoon stroll along the beach The Oar proved irresistible. The menu is simple and you can get coffee, alcohol or whatever, pizzas all day and meals at mealtimes. I guess it is connected to the resort there but it's open to all, laid back and friendly to grotty yachties A couple of tame ducks waddled amongst the few guests and were easily enticed with a few titbits. I noticed duck was also on the menu. Hmmm...

The anchorage is protected to the south and east and very calm.

You can walk about 1km along the beach to the East, or considerably further the other way. We chose the shorter walk to the east.

The sail here from Manta Ray Bay was an easy reach in a south easterly of about 15 kn. Beautiful sailing in flat waters and we topped 8 knots through the water, a bit less over the ground with the last of the tide against us. Once we got past Saddleback Island and into the lee of the mainland it became a magic carpet ride over completely flat water with a gentle 10 kn breeze that eventually fizzled to 5 knots around Gloucester Passage itself.

The only issue with getting here is you need to follow the navigation marks through Gloucester Passage: there is plenty of shallow water about. We came through at the bottom of the tide and found the shallowest water to be about 3.5m.

Gloucester Passage

Gloucester Passage

Stanley Reef

Donald likes rubber, I have discovered, especially in the form of a restraining strap. It improves his behaviour by evening out his excesses. He behaves with greater precision when I string a stretchy cord between the wheel and the side of the boat to give him something to work against and reduce the slight amount of free movement in the system to virtually zero. Donald, for those not familiar, is Anjea's untrustworthy autopilot. The problem is that the wheel is large and heavy, being constructed of stainless steel. It's a nice wheel to hold but Donald has to turn the wheel from below when he's in charge, and the inertia of the wheel causes a small degree of overshoot whenever Donald makes a course adjustment. This overshoot causes Donald to think the wheel has turned too far, so Donald turns it back, which again overshoots in the other direction, etc. The situation is vastly better since I bled the air out of the hydraulics but there is still a small amount of wobble and I am now on a mission to cure Donald of all impropriety; to reform him; to make him a perfect slave to our needs; quiet, unobtrusive, tweet-free and causing no ructions.

We are finally heading out to the reef. So far the only reef we've seen has been Lady Musgrave Island and Fitzroy Reef. While good, those reefs are a long way south and the further north you go the more spectacular the reef gets. The weather is OK today with 15 kn from the SSE. Initially the breeze is light and blowing off the land so it is from the west. We start to put up the MPS but it swings to the south, so we change to a spinnaker. The set goes well and I only make one mistake running the lazy brace inside the rail instead of outside, but that's easily remedied once we have it set.

The breeze rises through the morning and we drop the spinnaker for a poled-out jib as the breeze gets to a steady 16 kn. A bit more than our theoretical 15kn drop rule because the sea is pretty calm. Anjea is moving along at 7 to 8 knots and Donald, restrained by his rubber band, barely needs to make any effort to control the boat perfectly. We arrive at Stanley and anchor in 10m in time for a swim.

My first swim at Stanley Reef is to check the anchor. We are on the northern edge, next to the large 'river' that almost divides the reef, not quite turning the reef into an enormous lagoon. My first impression is not good: the ground is broken coral with small patches of coral sand. Luckily the anchor has dropped onto one of the sand patches and has dug in well without tangling any big bits of coral. I wonder about why the reef is so broken up. Is it because of the storms and cyclones that batter them? Or is it from the bad old days of fishing when trawlers could basically tear the reef apart looking for fish? I suspect this damage is due to storms as I can't imagine any trawling gear that could withstand coral to the extent required to do this sort of damage.

With confidence that the anchor is secure I get back in the dinghy and we motor over to some shallower reef. The lack of decent coral or fish on the first swim leaves me apprehensive, but as soon as I get in the shallow water I am greeted by clouds of small fish, a good start, and on closer examination, although the coral is broken up here too, there is lots of healthy coral growing everywhere it can. And then we start to notice the bigger fish: Lesley sees a family of coral trout, there are hundreds of what she thinks are called salmon, I see a giant groper staring at me from the distance. He is curious but wary. As soon as I swim in his direction he's gone with a flick of his tail. I guess you don't get to be a big fish by being too curious about humans. He was well over a metre long.

We enjoy the swim and spend the rest of the night fairly comfortably hanging off the anchor in about 12 knots of wind.

Big Broadhurst Reef

Lesley has a number of waypoints for dive and fishing spots through the reefs off Townsville. Several of these are for Big Broadhurst, and she also has satellite images of them to compare with the charts. The image quality isn't good though and we will still have to navigate by looking out the window. We fantasize about the day virtual reality will make it possible for anyone to do this in the safety of their home.

The sail north from Stanley Reef was gentle with the true wind at 165 degrees relative to the boat, at 10 knots, good for either a spinnaker or a poled out jib. We have got to the point where we can now select our sails by the numbers. Wind angles on a sail boat are measured in three ways and each has its application:

Apparent Wind is what the instruments at the top of the mast measure. It is the direction and strength of the wind relative to the boat, and so it measures what the sails actually see, with a bit of extra wobble thrown in because the measurement is from the top of the mast.

True Wind is how the wind would appear if the boat were stationary. In other words it is the Apparent Wind, minus the boat's speed and direction, minus the wobble. This is what we use to decide which sails to fly and when to reef. We could use Apparent Wind, but True Wind is much steadier and easier to read than Apparent Wind because the mast wobble has been subtracted (actually, I think it is just averaged out, but the effect is the same). As a point of interest, dinghy sailors don't experience mast wobble because they use body weight to balance the boat. They also continuously play the mainsheet to maintain a constant angle, so dinghy sailors sail to the apparent wind.

Wind Direction is the compass direction of the wind rather than the angle relative to the boat. We use this when checking the weather because this is the orientation that weather forecasts use. It is the True Wind angle minus the boat's heading.

Most people, when they hear the term 'true' in relation to an angle, such as True Wind Angle, think it means true vs magnetic. That is, the direction corrected for magnetic variation. But wind instrument manufacturers, in their wisdom, have (mis)appropriated the term 'true' to mean 'apparent wind corrected for boat motion'. It is a pity they could not have used a less confusing term, such as Corrected Wind.

We decided to pole out the jib in anticipation of stronger winds. 15 knots of wind is the limit of my spinnaker-flying expertise and we anticipate the breeze will build to more than that. The breeze came up as advertised, and duly carried us on to today's destination: Big Broadhurst Reef.

Big Broadhurst is appropriately named: it is about 3.5 miles across and 8.5 miles long, with a large, relatively deep, lagoon in the middle. It's a bit hard to see the reef edge as there is no drying reef, which is a bad sign because it means less protection from the sea. Although we have waypoints from others I am wary of using these and decide to make my own way using the charts as a guide and by eyes as the ultimate protection. Provided conditions are moderate and the time is between about 10AM and 4PM you can see shallow water quite easily before you hit anything. We come through the entrance into the lagoon in about 10m of water and I select an area of coral bommies on the south-western edge of the internal lagoon and set a course for them. The water gets deeper as we move inside the lagoon until we are in 30m. This is a bit worrying as 30m is getting a bit deep for anchoring.

Well past the point on the chart indicating 6m we are still in over 20m of water. At last we see some bommies and they look promising. Initially I am reluctant to anchor in water this deep but then I rationalize that the weather is forecast to be calm, the bottom is likely sand and broken coral, and we have plenty of chain so why not? On our first attempt I let out all 80 m of chain and one of the bommies ends up within our scope of swing so we decide on a quick exploratory dive and if it's worthwhile we'll move to a safer spot to anchor overnight.

We take the dinghy to the nearest bommie. Lesley gets in the water first to check the dinghy anchor. As she pops to the surface she has just one word: "Wow!". That turns out to be the only word we utter, every time we surface, for the next 15 minutes. The bommie is spectacular. It rises from the 20m bottom to just below the surface and has great crevices and caves all around. Clarity is ok (about 20m). The coral is fabulous -- old, layered and healthy. Fish are everywhere. We start a circumnavigation: the bommie is about 50m across and roughly circular. We get about half way around, exclaiming "Wow!" to each other every time we surface, when we spot a shark. Lesley identifies it as a bronze whaler. Not big, but definitely not to be trifled with. As we head back to the dinghy over the top of the bommie I suppress the thought of the shark chasing me all the way.

We will definitely stay to explore some other bommies, so we move the boat to a safer position and re-anchor without issues.

The Next Day

We have been waiting for this since Hobart, or at least Lesley has. We are on the Great Barrier Reef about 60 miles from Townsville and it's just about glassed out -- you can see the little puffy clouds reflected in the water. The only sound is the gentle slap of tiny wavelets lapping the hull; no wind whistling in the rigging, no other noises at all. And of course this is perfect for swimming and diving around the reef.

We decide on two dives: one in the late morning and another in the early afternoon. For the first dive we select the bommie closest to our new anchorage. It turns out to be just as spectacular as yesterday's dive. The only problem is anchoring the dinghy because there is very little shallow water with a sandy bottom. We eventually find a rubble-strewn crevice and manage to get the anchor down safely.

For the afternoon dive we head to the next closest bommie. It is quite small but has a sort of shallow, sandy lagoon inside which makes anchoring easy. This bommie is less spectacular than the others but we see a maori wrasse, a huge coral cod, more families of coral trout and many other fish. The one thing we don't see on either dive today is a shark.

Horseshoe Bay, Magnetic Island

We sailed directly from Big Broadhurst Reef to Horseshoe Bay on Magnetic Island near Townsville. Horseshoe Bay is a large, safe, comfortable bay good in anything from the east through south to the west. In other words, anything bjut a northerly. There is a convenience store ashore, some cafe's and restaurants, but no other services. It is possible to travel to Nellie Bay by bus and catch a ferry to the mainland from there but it's a long trip that is easier to accomplish by taking the yacht to Townsville Marina.

Before leaving Big Broadhurst we got a VHF weather forecast that seemed to say we could expect 25 knot wind on Saturday, today. As it turned out we didn't have enough breeze to sail, let alone 25 knots. So what went wrong?

Getting forecasts on VHF channel 22 was problematic. We only got occasional reception and it was sometimes so poor we couldn't make out what was said.

The 25 knots was forecast for 'offshore waters' which we assumed was us as we were 35 miles from the coast. It turns out the BOM definition of Great Barrier Reef Offshore Waters seems to be anything outside the reef. We were very much inside the outer edge of the reef, which is about 60 miles offshore. I think this was the major problem.

The GRIB weather file we downloaded a few days ago forecast 9 knots, about what we experienced. If we had followed that instead of trying to interpret the BOM forecast everything would have been fine.

There is a problem with BOM marine weather forecasts: they are way too general and broad. By necessity they have to be short, simple and cover a wide area. Really, they are just too simple to convey anything like the level of detail we've come to expect from a weather forecasts. Consequently, we are over-interpreting the little bit of data in every weather forecast.

The solution, I think, is to ignore VHF weather forecasts unless they are warning of storms, cyclones, cold fronts or other major events. Trying to squeeze detailed wind information from them will not work. For detailed weather we have a bundle of choices:

Windy, Predict Wind, Seabreeze, Google weather, Willy weather and many other websites all use data derived from one of the major global weather models. The alternative is to download a GRIB file and open it in your chart plotter. That way you get to see weather overlaying the area you are sailing, on the same chart. Perfect.

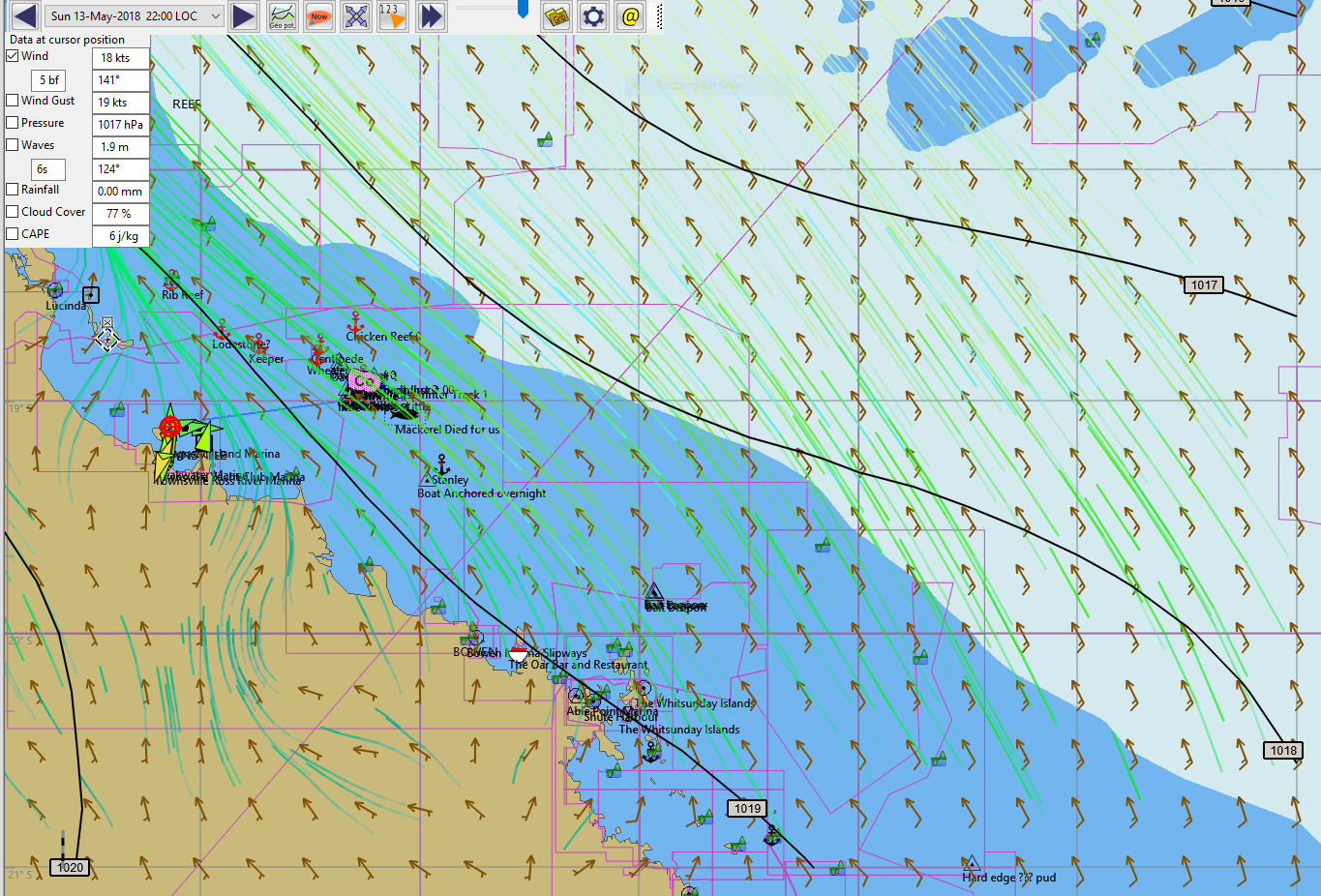

I use OpenCPN for navigation, which has good GRIB support using GRIB files downloaded from saildoc.com via email. The email interface is a little clunky but it is efficient. This is what I see:

An example of a GRIB file weather map over the top of a chart on OpenCPN

An example of a GRIB file weather map over the top of a chart on OpenCPN

I can choose to display a variety of different weather information, for 10 days or more into the future, overlayed on my CM93 charts, or I can turn it off. The screenshot shows pressure isobars, wind arrows and a particle map (wind flow, shown by the animated green lines)

Weather data in OpenCPN is limited to the GFS, COAMPS or RTOF models. GFS is the only one I have experience of.

GFS (Global Forecast System). US National Weather Service. This is a global model, which seems to be quite accurate for the Australian East Coast. Anyone who tells you their favorite model is better probably fails to realize that ALL weather models are constantly vying with each other to predict weather better than the others. The models themselves are constantly improving, the hardware they run on is constantly being upgraded and US government data is copyright-free, making GFS the basis of many other private forecasts that simply rebadge and design a pretty app for your iPhart or Mangleoid so they can charge you, or sell data about you to their advertisers.

COAMPS (Coupled Ocean/Atmosphere Mesoscale Predictions). A US Navy development that seems oriented to cyclone prediction. Never used it.

RTOFS (Real Time Ocean Forecast System). A US Navy sea surface temperature prediction model. Never used it.

The other major meteorological model is the European ECMWF model. I have never been able to find an easy-to-use source of GRIB data from this model and so have not used it. If you know of one then please let me know.